Article published in: June 2020

Authored by

DUNIA BRUNNER

Former Scientific Researcher,

Laboratory for Applied Circular Economy (LACE)*

Circular economy (CE) is today’s buzzword in discussions around sustainability. Often presented as an alternative to the current dominant “linear economy” model, it promises an economy where growth is decoupled from resource consumption and pollutant emissions.

Inspired by nature, CE replaces the “take-make-dispose” or “extract-produce-consume-trash” approach, by a (eco-) systemic one, where end-of-life materials are conceived as resources rather than waste and the use of toxic chemicals is eliminated. It is restorative or regenerative by intention and design1. In a nutshell, CE is based on the following principles:

- Design out waste and pollution

- Keep products and materials in use for an extended period (i.e. slow cycles)

- Restore or regenerate natural systems by intention and design

- Minimize raw material extraction and waste generation

BUILDING ON ECONOMIC, NATURAL AND SOCIAL CAPITAL

Most agree that the current linear model is no longer fit for purpose, failing both people and the planet. Approximately 50 years ago, when confronted with the consequences of exponential economic and demographic growth, people started realizing that the earth is comparable to a “spaceship” with limited resources and limited capacity to absorb pollutants and emissions2. Thus, different approaches were developed that adopted a systemic view to best manage resource flows, in an essentially closed system (e.g. industrial ecology, clean technology, cradle-to-cradle™, blue economy, performance economy, biomimicry, etc.).

CE is largely inspired by these schools of thought. Despite its blurry contours and various definitions3, CE’s concern is to enable economic and social prosperity within the planetary (almost) closed ecosystem, for sustainability and profitability in the long run. The book Waste to Wealth by Peter Lacy and Jakob Rutqvist, published in 2015, estimates to 4.5 trillion the business opportunities to be unlocked from circular business models.

REDUCE, REUSE AND RECYCLE

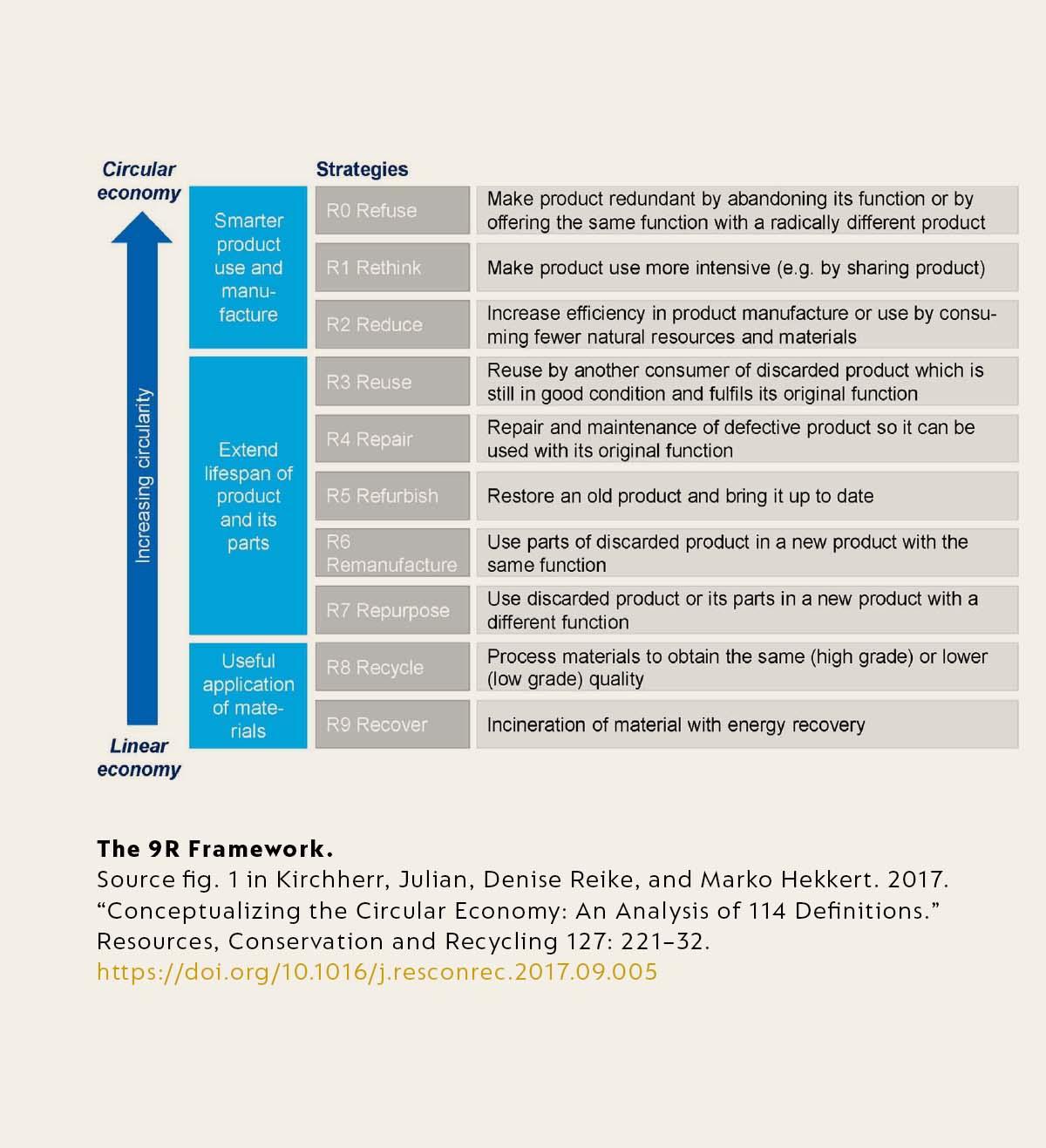

The different strategies for implementing the main principles of CE are often described along variations of the “R framework”: from 3Rs (reduce, reuse, recycle), to 6Rs or even 9Rs (refuse, rethink, reduce, reuse, repair, refurbish, remanufacture, repurpose, recycle, recover)4. These represent the ‘how-to’ of CE, translating the intent of making the best possible use of materials and energy, namely by working towards closed loop systems.

5 CIRCULAR ECONOMY BUSINESS MODELS

Accenture has identified 5 business models for companies adopting CE based on their position in a value chain:

1. Product as a service models: focus on selling a service rather than a product.

2. Leasing models: creating incentives for designing and building longer lasting products, as the company bears the cost of usage and maintenance.

3. Sharing models: enable increased utilisation rate of products by making possible shared use / access / ownership.

4. Eco-design product: concentrate on integrating ecological aspects into key activities and value proposition.

5. Resource recovery models: recover materials, resources and energy from disposed products or by-products for instance: co-product generation, industrial symbiosis, as well as take-back management and reverse logistics5.

Circularity often entails reorganization along the supply chain, so that patterns related to upstream or downstream components of a business model can be very relevant for CE. As there is no universal or ideal "circular" business model, each company has the flexibility to create the most suitable model for its specific situation.

REALISING THE POTENTIAL OF THE CIRCULAR ECONOMY

Despite the great potential of transitioning to a CE being largely accepted, there is still a huge gap of circular opportunities being wasted6. Various barriers, often grouped into four main categories, explain this discrepancy:

1. Technical or technological factors

2. Economic/market factors

(e.g. high upfront initial costs and market uncertainty limit new investments, inertia and lock-in, strong path-dependencies of the prevailing socio-technical systems)

3. Institutional and regulatory factors

(e.g. high tax on labour, lack of green public procurement schemes, lack of subsidies, lack of clear aims and targets, etc.)

4. Social and cultural factors

(e.g. risk-aversion, reluctance to change, etc.)

The relationship that these factors have with one another considerably impacts the complexity at stake. For example, market-relevant factors can prevent political and thus legal changes, which in turn prevent market efforts towards new and innovative cycle-oriented business model innovations and hinder change in consumer behaviour. The described interdependence does not only move in one direction and can be seen as one with reciprocal potential7.

A COLLECTIVE CHALLENGE

Building a prosperous CE within our planet's limits represents a major transformation, which implies changes in the current consumption and production patterns and questions deep-anchored routines and world-views8.

Confronted with this, some actors are hesitant to adapt, and wait for others. On the other hand, this can also lead to a chain reaction – where the move of one actor may encourage others to follow suit.

TOWARDS TRULY SUSTAINABLE BUSINESSES

Companies have a key role to play as effective implementing bodies of CE. In addition to inciting a great virtuous cycle, they could benefit from the innovation potential of solutions developed to overcome the current barriers.

By integrating environmental and social factors into their business models, companies can convert sustainability and social challenges into business opportunities and become “Truly Sustainable Businesses”9.

View all references